An Introduction to Georgian Qvevri Wine in Zagreb

Reading Time: [est_time] For a listing of articles and videos on Georgian wine and other wines from the Caucasus region, check out our page Uncorking the Caucasus. To purchase the Kindle or paperback copy of the book Uncorking

Reading Time: 6 minutes

For a listing of articles and videos on Georgian wine and other wines from the Caucasus region, check out our page Uncorking the Caucasus. To purchase the Kindle or paperback copy of the book Uncorking the Caucasus: Wines from Turkey, Armenia, and Georgia, please head to this Amazon product page.

Georgia, the Country of Ancient Winemaking

At the intersection between Eastern Europe and Western Asia lies an important key to the origins of wine: Georgia. It is a mountainous country that has survived many millennia of conflicts and somehow managed to hang on to its traditions including its love for wine.

In Georgia, wine production has been going on uninterrupted for 8,000 years. The qvevri is the symbol of Georgian winemaking. As early as in the Neolithic age, grape juice was fermented in buried qvevri. It is fascinating that thousands of years later, Georgia is still making wine in the same way as it did in the past. For that reason, drinking Georgian qvevri wine is similar to tasting the flavors of the ancient past. The Georgians who make wine in qvevri believe in the laissez-faire approach, where nothing is added and nothing is taken away. By putting the grapes into a qvevri and burying it underground, the winemaker allows nature to do most of the work.

What is Qvevri?

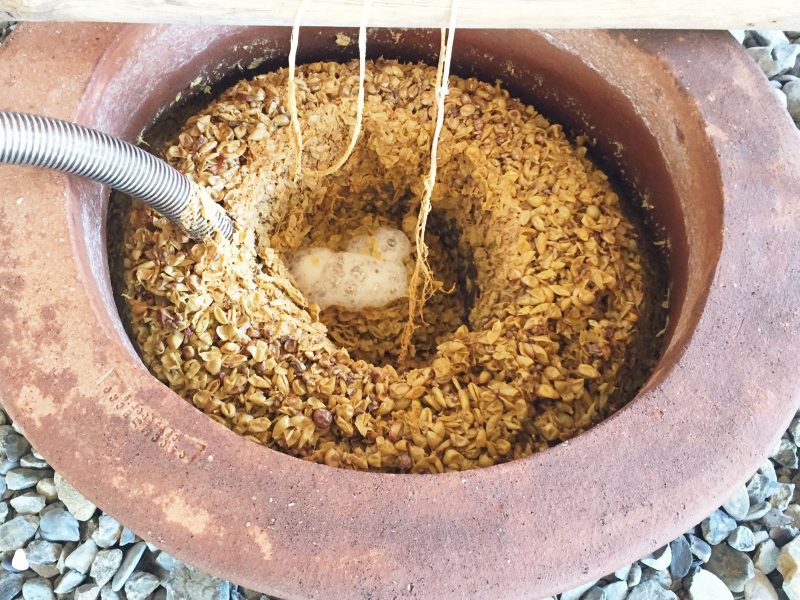

The qvevri (pronounce “kway-vree”) is an egg-shaped, beeswax-lined terracotta vessel used for making wine. The qvevri is filled with grapes, their skins and pips, and sometimes the stems too. Fermentation in the open qvevri relies on wild yeast. Geothermal regulation keeps the fermentation and wine at a constant, cool temperature. As the wine ferments, the qvevri’s conical shape promotes circulation and clarifies the wine naturally. After fermentation, the qvevri is sealed with a wooden lid and beeswax or clay. They are opened anywhere between a few months and a few years later for the wine to be transferred into another qvevri or bottles for further aging, or to be consumed immediately.

Outside of Gerogia, it is more common in the wine industry to use the term anfora or amphora (amphorae for plural) to refer to the clay vessel used for making wine. However, in Georgia, it is important to call a qvevri a qvevri as it is a symbol of their culture. In 2013, the UNESCO declared Georgia’s ancient tradition of making wine in qvevri as an Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Qvevri found outside the Pheasant’s Tears winery in Kakheti, Georgia. The size of qvevri can range from a few hundred to thousands of liters.

What is Orange Wine?

Let’s get this straight first: in Georgia, it is more common for people to refer to this style of wine as amber wine. We, too, prefer to use the term amber wine. However, outside of Georgia, people generally call it orange wine.

Nothing to do with the citrus fruit, orange wine is made from white wine grapes. While white wine is fermented from white grape juice with little to no skin contact, orange wine is fermented with the skins and seeds, and sometimes even with the stems. The color of a wine comes less from the flesh and juice than from the skin. For that reason, the skins of white grapes impart an amber hue to orange wine.

Besides imparting color, the seeds, skins, and stems provide tannins—a dry, grippy quality found in some red wines—to orange wine. When drinking orange wine, expect the slight astringency of a red wine and the crispness of a white. Just like all other wines, orange wines differ widely depending on the grape variety, terroir, and winemaking style. But as a general guide, they are medium- to full- bodied, with robust characteristics of nuts, tea, and dried fruit. By virtue of its bold flavors, medium to high acidity, low alcohol, and significant body, it can be paired perfectly with various dishes—from the spicy, to umami, and salty.

Today, orange wine is being made in all parts of the world including Australia, Austria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, France, Italy, Mexico, Slovenia, and the United States.

Introducing Georgian Qvevri Wine to Croatian Wine Lovers

After several months of promoting our book Uncorking the Caucasus in Georgia and Armenia, we finally left the region in November and made a brief detour to Macedonia to attend the inaugural Skopje Wine Salon (organized by our dear friend Ivana Simjanovska), before returning to Croatia. From Tbilisi the capital of Georgia, we brought along four bottles of Georgian qvevri wines that we were planning to share with a special group of wine lovers in Croatia. The group consisted of the top Vivino users in Croatia as well as Nenad Trifunović, an established wine blogger who runs the website vinopija.com (in Croatian).

While not new to amber wine (there are several Croatian winemakers who are making white wine with some skin contact), this was the first time that all eight Croatian wine lovers are tasting Georgian amber wine made in the qvevri.

Our Selection of Georgian Qvevri Wines

The wines were served in an intentional sequence: from a few days of skin contact (something we expect everyone will enjoy) to deep amber, tannic wine that saw many months of skin contact (something that challenges conventional beliefs).

Nikoladzeebis Marani, Tsitska-Tsolikouri, 2015

Winemaker: Ramaz Nikoladze

Miscellaneous Notes: Ramaz Nikoladze is one of the big names in Georgia. He makes only around 3,000 bottles every year. His Tsolikouri was selected by Carla Capalbo as the Favourite Wine of 2015 at the Decanter’s 40th Anniversary celebration. For a mammoth-looking guy, his wines are surprisingly gentle.

Tasting Notes: Prominent but workable volatile acidity that flatters the aroma of dried flower and ripe apricot. A little volatile acidity really highlights the typical ripe or dried fruit flavor of amber wine; too much will obviously swamp the beauty. Gentle tannins and green tea-like astringency hit the mid-end palate. A delicate amber wine that makes a safe introduction for those who are new to this wonderful world of skin contact.

With winemaker Ramaz Nikoladze at Vino Underground in Tbilisi, Georgia.

Gotsa Family Wines, Chinuri, 2015

Winemaker: Beka Gotsadze

Miscellaneous Notes: Recently, Beka pioneered a heat treatment system to clean his qvevri and combat the big, bad brett—most commonly known as the “funky smell” in amber wine. He’s also one of the few winemakers in Georgia who is currently making pét-nat wines. The first vintage of his pét-nat was released in December 2016.

Tasting Notes: Allegedly one of the most popular wines to be served at the recent RAW WINE New York 2016. Tropical juiciness perked up by summer citrus brims the nose! What fun! The flavors are juicy, too, in the mouth and flawlessly moves into an imminent white-tea finish. A touch of gingery bitterness lingers. This is an amber wine that can be easily dismissed as simple and approachable, but start shifting attention to the structure and transition, let it aerate for awhile, and you can find many nuances to it.

Gotsa winery’s Beka Gotsadze opening a bottle of pét-nat that is still fermenting in the bottle. Do not try this at home. Seriously.

Lagvinari, Goruli Mtsvane, 2013

Winemaker: Dr Eko Glonti

Miscellaneous Notes: Cardiovascular surgeon-turned-geologist-turned-winemaker, Eko is arguably our favorite wine producer in Georgia. He started making wine five years ago with the encouragement of Isabelle Legeron MW (organizer of RAW WINE).

Tasting Notes: The smell of a Chinese celebration—goji berry, gooseberry, orange peel, fig, and an undefined red fruit underlying. The palate reflects the nose with complementary tannins that outline the ripe fruit notes.

The Lagvinari wine cellar is located in the basement of Dr Eko Glonti’s house in Tbilisi, Georgia. Here’s him selecting the treats for the evening.

Tsikhelishvili Wines, Rkatsiteli, 2013

Winemaker: Aleksi Tsikhelishvili

Miscellaneous Notes: No background information as we haven’t got the chance to visit the winery.

Tasting Notes: Raisin and prune on the nose. Sherry-like with pronounced volatile acidity. Almost hard to differentiate from a red wine if tasted blind. The front palate is gentle and the body is medium. When the wine sets in the mouth, draw some air in and you’ll notice the citrus and stone fruit flavors along with tannins hitting hard on the mid palate, defying the earlier assumption that it could be a light red. A powerful amber wine with black tea-like astringency and mouth-coating ripe fruit flavors.

We didn’t get the chance to visit the Tsikhelishvili’s winery yet, but this was the night when we fell in love with his wine. We were having dinner at Azarphesha restaurant in Tbilisi and our dear friend John Wurdeman picked out a bottle of Tsikhelishvili Rkatsiteli for us to try.

Georgian Qvevri Wine Against the Croatian Palate

Many of our Croatian friends commented on how “alive” and how much “energy” the Georgian qvevri wines possessed.

We continued the night with a blind tasting of six different varietal red wines made out of Teran, an indigenous variety from Istria, Croatia; the round-up will be shared in a future article. As for the qvevri wine tasting: surprisingly, it was the last bottle, Tsikhelishvili Wines Rkatsiteli 2013, that was crowned the favorite of the night. We said “surprisingly” because we had assumed that the wine would be the most difficult to understand—with its extreme oxidative style, black tea-like tannins, and dried fruit characteristics. As it turned out, most people appreciated that wine most because it reminded them of a red wine. Overall, everyone enjoyed at least two out of the four wines, except one person who drinks only reds. Many of our Croatian friends commented on how “alive” and how much “energy” the Georgian qvevri wines possessed. We were delighted with the way the wines showed overall.

One of our favorite things to do is introducing new wines to enthusiasts and experienced palates. It is always fun to share gems from the unheralded regions of the wine world with fellow wine lovers. Georgian qvevri wines are the most fun, yet challenging, to present to wine lovers. When these wines are done well, they give flavors and experiences that are unparalleled. At a time when words like “raw wine”, “natural wine”, and “wine with a sense of place” are gaining traction on the world stage, the Georgian wines are the perfect candidate to offer diversity and novelty that can’t be found anywhere else in the world.

You May Also Enjoy

The Unstoppable Progress in the Georgian Wine Scene

Saperavi: Georgia’s Flagship Red Wine Grape

A Brief History of Wines from the Caucasus

UNESCO: Ancient Georgian traditional Qvevri wine-making method

Special thanks to Bornstein Wine Bar and Shop for hosting us.

The ideas expressed in this article are personal opinions and are not associated with any sponsors or business promotions.